More than just getting old: The hidden signs of osteoarthritis in dogs

Many dog owners are familiar with this moment: their once energetic four-legged friend suddenly no longer jumps into the car with joy, takes a little longer to get going on walks, or simply seems "more laid-back" than before. Behind such subtle changes is often a condition that causes much more than just "old age stiffness": osteoarthritis, better known as arthrosis. It is one of the most common chronic joint diseases in dogs and affects up to one in five four-legged friends. The signs are usually subtle, develop slowly, and are therefore often dismissed as "he's just getting old."

This article shows you why that's not true—and how you can recognize the subtle signs early on to give your dog a more pain-free, active life.

Frequency

Up to 20% of all dogs are affected.

Susceptible animals

especially large dog breeds

Symptoms

Reluctance to move, difficulty getting up, initial lameness

Treatment

No cure, but a better quality of life through multimodal therapy

What is osteoarthritis?

Osteoarthritis is a chronic degeneration of the joint cartilage, resulting in progressive cartilage breakdown. The affected joint gradually loses mobility and causes pain.

Osteoarthritis can be caused by:

- Developmental joint malformations (e.g., HD/ED)

- Trauma or injuries (e.g., after a cruciate ligament rupture)

- infections

- Immune-mediated joint diseases

- Aging processes (natural degeneration)

Racial predisposition and affected joints

There is indeed a breed predisposition among large, heavy, and stocky dogs. Labrador Retrievers, Golden Retrievers, German Shepherds, and Bernese Mountain Dogs are particularly affected . Whippets and Greyhounds are the least affected, as they are slim, light-footed, and have very well-coordinated movements.

The hip, elbow, and knee are most commonly affected, but osteoarthritis can affect any joint.

Recognize signs

The symptoms are often overlooked and misinterpreted as a normal part of the aging process. Classic lameness is particularly noticeable after getting up and improves after a short period of movement.

A dog that used to enthusiastically run up stairs or was almost impossible to slow down when playing suddenly becomes more cautious, calmer, or less persistent. Many dogs lie down more often, play less, refuse to jump, hesitate when getting up, or simply seem "unenthusiastic." Some react more irritably, others withdraw or seek less physical closeness than before. These changes often seem like the normal passage of time—but in reality, they are silent coping strategies of an animal in pain.

diagnosis

If you have noticed any of these signs in your dog, it is worth visiting the vet. A clinical and orthopedic examination will help to narrow down the clinical picture. The veterinarian may detect thickening of the affected joint, reduced mobility, or even muscle wasting. X-rays may also be taken. Typical signs of osteoarthritis on X-rays often include joint effusion, periarticular swelling, osteophytes (bone spurs), subchondral sclerosis, and partial narrowing of the joint space.

Therapy: a multimodal approach

One of the most important things to know is that osteoarthritis is unfortunately incurable. Once damaged, joint cartilage cannot regenerate. However, this diagnosis is by no means a reason to give up. The aim of treatment is not to reverse the damage, but to keep the dog as pain-free and mobile as possible. The aim is to control the inflammation, maintain mobility, and slow down the progression of the disease.

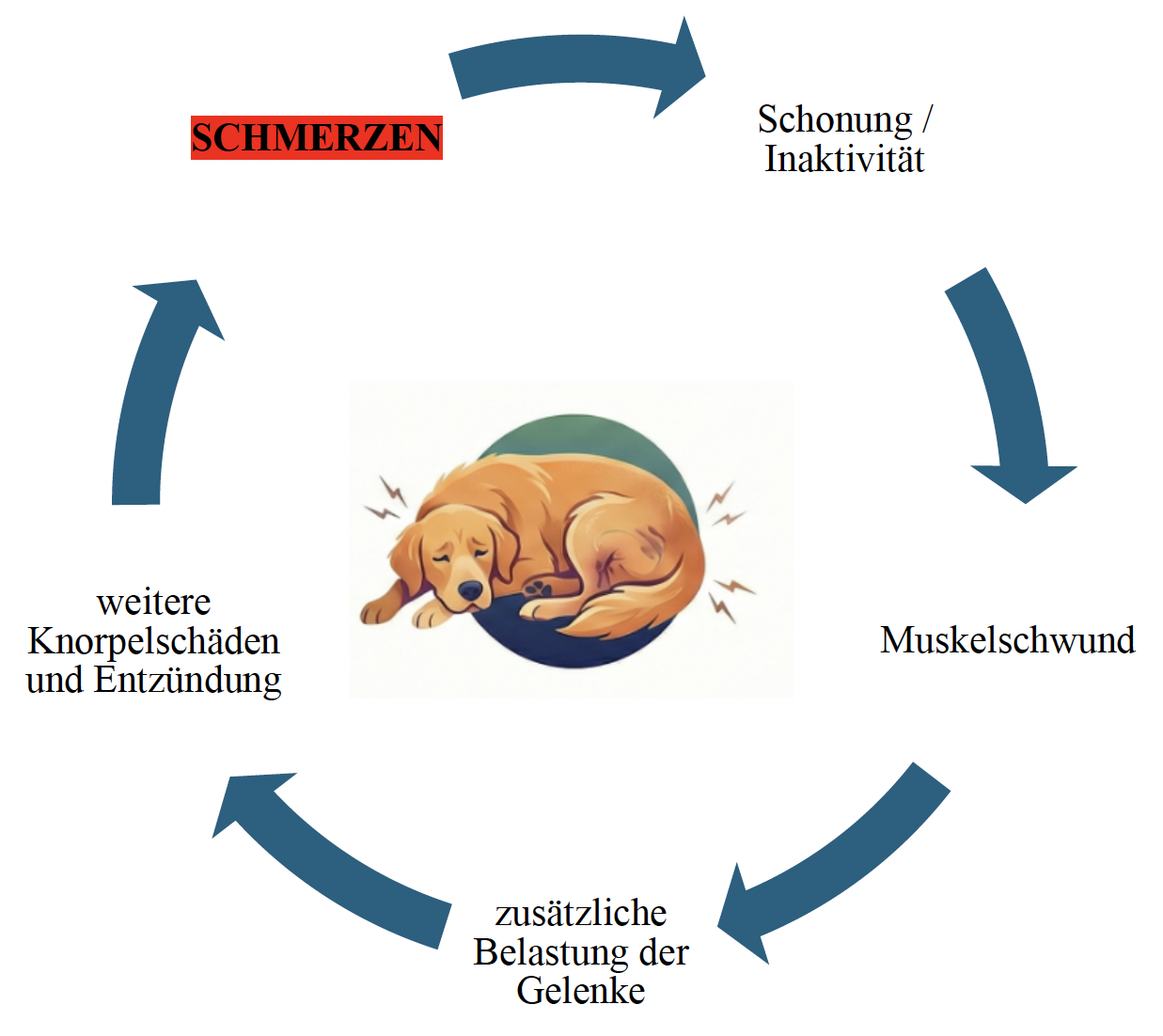

A joint that hurts due to osteoarthritis is automatically spared by the dog. It moves less to avoid pain. However, this inactivity gradually causes the muscles to deteriorate. Weaker muscles no longer stabilize the affected joint sufficiently, which increases the strain on the joint capsule, cartilage, and ligaments. This leads to further cartilage damage and new inflammation. The pain increases again—and the cycle begins all over again.

Many owners believe that rest is helpful, but in the long term it actually worsens the condition. Breaking this cycle of pain is central to the treatment. Modern painkillers play a key role in this. In addition to classic anti-inflammatory drugs, antibody therapies are now also available, which deliver very good results, especially for chronic pain. In addition, there are local joint infiltrations or surgical measures that may be useful in certain cases.

At the same time, physical therapy plays an important role. Targeted exercises, mobilization techniques, and the development of stabilizing muscles relieve pressure on the affected joint and keep it mobile. The dog's body weight is also a key factor, as every extra pound puts additional strain on the joints. Certain nutrients such as glucosamine, chondroitin, or omega-3 fatty acids can also support the treatment. Some owners are also interested in homeopathy or alternative methods such as laser, acupuncture, or magnetic field therapy. Individual dogs experience an improvement in their well-being through these complementary medical therapies; however, it is important that such approaches are only ever used as a supplement—never as the sole therapy if the dog is in pain.

If your dog is overweight, controlled weight loss is one of the most effective measures to alleviate the symptoms. Every extra pound puts significantly more strain on joints that are already painful.

Osteoarthritis is more than just a sign of aging. It is a serious, painful condition that often goes undiagnosed because its symptoms are subtle and insidious. It is worth taking a closer look. If your dog has recently shown less enthusiasm for exercise, avoids certain activities, or you notice that he has changed, there may be more to it than just age-related fatigue. The most important question remains: what to do? In such cases, talking to your veterinarian is the best next step. You are your dog's most important voice—and with timely support, they can lead a happy, active, and pain-free life despite osteoarthritis.

From pet parents for pet parents

The health of your furry nose is our job